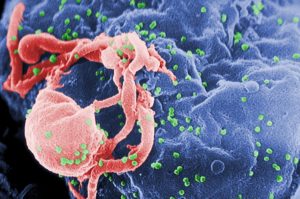

Scientists have made important inroads in understanding why patients with HIV develop neurological disorders despite treatments that otherwise hold the virus at bay. The project was made possible with SMRT Sequencing, which generates reads long enough to span the full HIV envelope.

“Ultradeep single-molecule real-time sequencing of HIV envelope reveals complete compartmentalization of highly macrophage-tropic R5 proviral variants in brain and CXCR4-using variants in immune and peripheral tissues” was recently published in the Journal of NeuroVirology by lead author Robin Brese, senior author Susanna Lamers, and collaborators at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and Bioinfoexperts. In the article, the team describes a novel approach for examining how HIV evolves in the brain, segregated from HIV replicating in peripheral tissues. This may explain why the virus continues to attack the brain even when viral load in the rest of the body is controlled with antiretroviral therapy.

Analyzing individual virus genomes has been the preferred method for studying this phenomenon, but doing so with short-read sequencers “is problematic with HIV because millions of short sequences are generated, which subsequently require assembly, a near impossible feat with HIV [envelope] due to its high sequence variability combined with the error rate of NGS,” the scientists report. For this study, the researchers used SMRT Sequencing to generate full-length sequences of the HIV envelope, eliminating the need for assembly. Tissue samples came from a deceased, 43-year-old male HIV patient who had been responding well to drug therapy but had been diagnosed with HIV-associated dementia. Samples were collected from brain, lymph node, lung, and colon.

Scientists generated full-length envelope sequences — spanning about 2.6 kb each — and aligned nearly 53,000 unique reads. They developed phylogenetic trees showing “that brain-derived viruses were compartmentalized from virus in tissues outside the brain with high branch support,” the team writes. They further add that “variants from all peripheral tissues were intermixed on the tree but independent of the brain clades.” Finally, they note that the depth of sequencing and variation found within the brain samples was compelling, and that “SMRT did not simply reamplify thousands of sequences that were derived from a single or very few proviruses, but likely reflects the true diversity in the tissue.” Interestingly, CXCR4-using variants were found only outside the brain, while viruses within the brain used the CCR5 co-receptor.

“The study is the first to use a SMRT sequencing approach to study HIV compartmentalization in tissues and supports other reports of limited trafficking between brain and non-brain sequences during [combined antiretroviral therapy],” the scientists conclude. “Due to the long sequence length, we could observe changes along the entire envelope gene, likely caused by differential selective pressure in the brain that may contribute to neurological disease.”