Customer Success Story

Experts at Children's Mercy Kansas City Turn to Long-Read Whole Genome Sequencing to Find Answers for Rare Diseases

Children with complex rare diseases are at the forefront of clinical research discoveries at Children’s Mercy Kansas City as scientists move beyond microarrays and exomes to enable improved care.

- ChallengeScientists at the Children’s Mercy Research Institute (CMRI) are striving to provide answers to rare diseases that have not been found using conventional sequencing approaches.

- OpportunityThe adoption of highly accurate long-read sequencing technology is enabling the research team at the CMRI to identify causative genetic variants that have been previously missed.

- ProgressIn the midst of sequencing of the first 80 genomes using the Sequel II System, the team has already captured novel pathogenic variants— including structural variants.

- FutureBased on these early successes and to expand research capability into potential disease-causing variants in children with rare disease, the CMRI has scaled up their sequencing capacity to include six Sequel IIe Systems for up to 1,000 complete genomes per year.

The Odyssey for Answers to Rare Diseases

By the time families of children with an undiagnosed rare disease reach the experts at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, one of the nation’s premier pediatric medical systems, many of them have already spent years on an exhausting quest to find the cause of their child’s illness. Some of those medical journeys have been so long that the kids with rare disease are now adults, still searching for a diagnosis.

“We work with families that are struggling and we’re trying to provide them the answer that they need,” says Emily Farrow, Director of Laboratory Operations at the hospital’s extensive Genomic Medical Center.

Children’s Mercy Kansas City serves a large geographic area of the U.S. heartland, filling a need for rare disease expertise and cutting-edge genomic infrastructure away from biotech hubs on the coasts and in large cities. The institution is home to the Genomic Answers for Kids (GA4K) rare disease program, which aims to collect genomic data and health information for 30,000 children and their families over the next seven years, as well as the new Children’s Mercy Research Institute, a sprawling facility with state-of-the-art laboratories designed to support a collaborative approach to healthcare and research. Scientists at Children’s Mercy also work closely with other hospitals around the world, deploying their research expertise for investigators in need.

To investigate non-diagnostic cases, the GA4K team has a broad array of tests and technologies at its disposal. Recently, they incorporated PacBio highly accurate long-read sequencing, known as HiFi sequencing, to help identify the underlying genetic causes that have previously been undetectable using conventional methods such as microarrays and exome sequencing.

Why Are Rare Diseases So Challenging to Solve?

Rare diseases can be virtually impossible to diagnose as clinicians see so few people with any single rare condition and the underlying genetic mechanisms of many rare diseases remain unknown. Collectively, rare disease is not rare, affecting many people. It’s estimated that as many as 30 million Americans and more than 400 million people globally are affected by a rare condition. An estimated 7,000 rare diseases are recognized, with new ones discovered regularly. Unfortunately, rare diseases often affect children, and are responsible for about 20% of infant deaths in the U.S.

Rare Disease at a Glance

Although each individual disease is rare—occurring with low frequency in the population—collectively rare diseases are quite common, and present unique challenges to diagnose. Learn more from Global Genes.

Most rare diseases have a genetic cause, and pinpointing that cause allows for both a concrete diagnosis and potentially a plan for treatment. But finding the genetic element responsible for an individual’s rare disease is not straightforward.

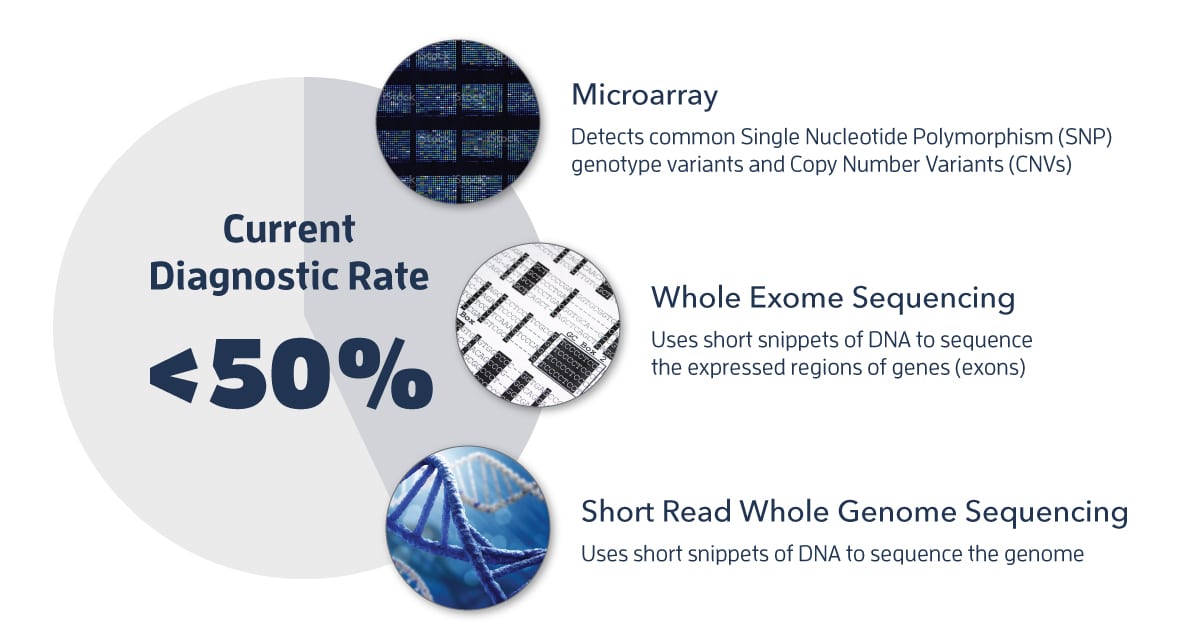

While next generation DNA sequencing has led to significant progress in diagnosing rare disease, exome sequencing and genome sequencing based on short-read technologies lead to diagnoses in less than 50% of cases. For the majority of rare disease cases analyzed with short-read data, the causal variant is not identified.

Conventional Techniques for Identifying Pathogenic Variants

So where are all the other pathogenic variants hiding? Dr. Tomi Pastinen, Director of the Center for Pediatric Genomic Medicine at Children’s Mercy, says there are two categories of challenging variants: those we can see but can’t interpret, and those we can’t see at all using conventional techniques. The former group includes genomic regions beyond the exome.

“Whenever we are outside of the coding regions, we are in trouble,” he says. For some diseases, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, he notes that causal intronic variants have been found and are now part of routine clinical testing. But in general, noncoding regions have not received the same level of scrutiny as the exome, leaving even experts to guess at the function of variants in those areas. These mysteries will only be solved by intensive genomic studies designed to shed light on noncoding regions.

The second group — variants that are missed by conventional technologies — represents a more tractable problem. Scientists know that certain types of variants tend to escape detection by microarrays and short-read sequencing platforms. These structural variants include large deletions and insertions, repeat expansions, translocations, and more. They’re too complex or too rare to find with microarrays and too large to capture fully with short reads. For all of these variants, Dr. Pastinen says, it’s essential not only to detect them, but to characterize them with base-pair resolution.

Applying HiFi Sequencing to the Most Challenging Rare Disease Cases

Unlike the data produced by short-read sequencing platforms, which are typically used for exome or whole genome sequencing, HiFi sequencing data comes from extremely long reads that span even the largest structural variants. HiFi sequencing provides the most comprehensive view of variation in a genome, replicating the variation found with short reads, and detecting the larger and more complex variants that short reads can’t detect.

What is HiFi Sequencing?

HiFi sequencing is a type of long-read sequencing that is characterized by its high accuracy. Together, long read lengths and high accuracy provide very complete genome assemblies, comprehensive variant detection, and phasing to represent maternal and paternal haplotypes. Learn more about HiFi Sequencing.

When the Children’s Mercy team was looking for a new way to research the underlying genetics of rare diseases that remained unsolved after short-read exome or whole genome sequencing, they turned to HiFi sequencing from PacBio in the hopes of accessing some of the variants invisible to other approaches. “Our internal research experience has given us a very good understanding that performing whole genome sequencing with short-read sequencing technology is not going to solve the cases that were not solved by exome sequencing,” Dr. Pastinen says.

Consequently, they deployed HiFi sequencing for some of the toughest situations: children for whom parental genomes were unavailable, or where potentially large or complex pathogenic variants were believed to be hidden among highly repetitive sequence or in areas of low coverage for short-read data.

GA4K – Building the Future of Genomic Medical Research

Children’s Mercy scientists evaluated HiFi sequencing as part of their GA4K effort, which is ultimately expected to generate a first-of-its-kind, open-access clinical data repository of nearly 100,000 genomes. But their goal goes well beyond amassing genomic data — it’s about providing answers. “We know that if the genomic basis for the family’s mystery remains unsolved, they’ll bounce back to us again when another member of that family is affected,” Dr. Pastinen states.

For a pilot project, Children’s Mercy scientists analyzed 80 genomes. Being able to generate high-quality, fully phased de novo assemblies eliminates the need for trio sequencing, streamlining the process of analyzing an individual’s genome. Already, the team has found instances “where PacBio captures a pathogenic variant that other platforms can’t see,” Dr. Pastinen says.

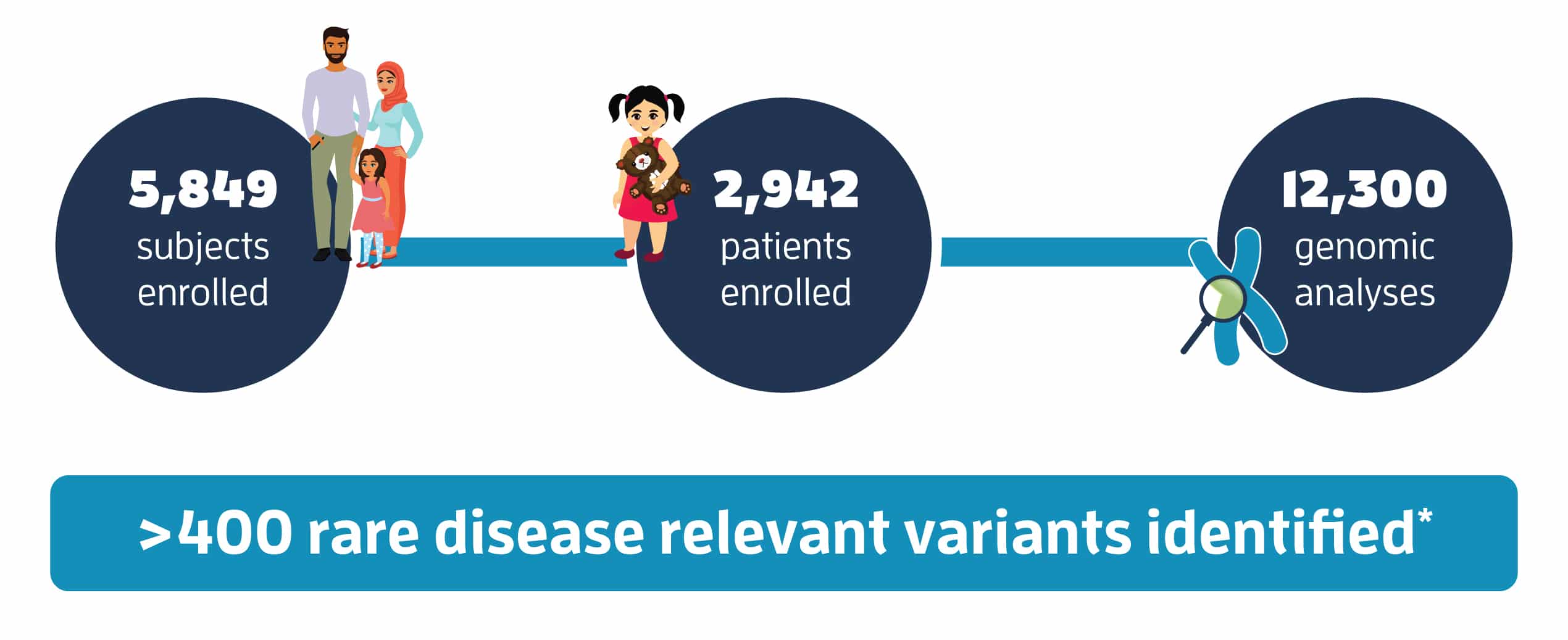

Genomic Answers for Kids

Project Progress

A snapshot of the extensive sequencing project GA4K has undertaken and progress toward providing families answers through genomic insights. *Study results as of April 2021

In the genomic analysis of an individual with developmental delays and seizures, HiFi sequencing revealed a pathogenic variant in a region that proved difficult for short reads to represent accurately. In another example, a four-year-old girl with hepatosplenomegaly whose parental genomes were not available for analysis was biochemically diagnosed with Niemann Pick disease Type C. HiFi reads showed two key variants located on different alleles of the relevant gene; with the phased variants, scientists were able to explain the underlying genomics of the disease.

In a large family with a challenging phenotype that includes dystonia, HiFi sequencing identified a five-base repeat insertion of up to a kilobase that was present in affected individuals but not in unaffected members of the family. This kind of result “is not only highlighting the power of the long-read sequencing in recognizing these pentameric expansions,” says Dr. Farrow, “but it’s also highlighting the importance of continuing to generate control data sets so that we can begin to evaluate what’s normal from something that might be disease-associated.”

Hear Dr. Pastinen describe the impact of the Genomic Answers for Kids project in the video below:

The HiFi sequencing approach also lets scientists like Dr. Farrow streamline the process of getting to an answer. Traditionally, rare disease cases might be interrogated with multiple methodologies, including microarrays, expansion testing, and exome sequencing to capture as much information as possible. “One of the things that we’re really excited about is that you could answer all three of those questions with one long-read sequencing platform,” she says.

Scaling Up and Moving Forward

Getting to the point where HiFi sequencing could contribute answers to rare disease cases has taken a lot of community effort, Dr. Pastinen says. As the sequencing technology itself became more affordable and higher-throughput, he says, the development of bioinformatics tools and major research efforts such as the Telomere-to-Telomere Consortium and the Human Pangenome Reference Initiative “have built up a data resource that actually makes it possible to start to compare patient genomes in a meaningful manner.” But there’s more work to do, he adds, noting that there will need to be a community resource like gnomAD focused on long-read sequencing data to improve variant interpretation.

The Children’s Mercy team is scaling up too as the group aims to use HiFi sequencing for research into approximately 1,000 cases that were unexplained after the preliminary short-read exome analysis. To accomplish this, the rare disease research team has tripled its PacBio sequencing capacity to ramp up their GA4K efforts and to meet the needs of new collaborations with other hospitals. These instruments will be housed in the new Children’s Mercy Research Institute, a nine-story, 375,000-square-foot building dedicated to advancing care for complex childhood diseases.

“It’s really an exciting time, and we’re fortunate to have all of these tools and technologies to answer these rare disease questions,” Dr. Farrow says.

Explore These Additional Rare Disease Resources

Talk with an expert

If you have a question, need to check the status of an order, or are interested in purchasing an instrument, we're here to help.